By Francisco Laborde

English Trans. by Ma. Teresa Vidaurre

It would be comforting

that all living creatures

of the sky and earth

would have to perish

in great grief.

Takeo Takahashi[1]

Introduction

After six months of bombarding intensively 67 cities of the Japanese Empire, Harry Truman, the United States President, activated the Manhattan Project. He ordered to launch nuclear weapons over Japan, and on August 6, 1945, on a Monday, the uranium bomb code-named Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima, followed on Thursday by the detonation of the plutonium bomb code-named Fat Man over Nagasaki. Shortly after the explosions, Japanese scientists from varied fields entered the bombarded cities. On August 10, Japan confirmed that the U.S.A. had dropped atomic bombs during a meeting of the Navy backed by the Imperial General Headquarters. On August 15, 1945, The Japanese Empire announced its surrender to the Allies.

Kenzaburo Oé was not only a renowned fiction writer, but he was also a chronicler, and as such, he visited Hiroshima every year on the anniversary of the atomic bomb explosion, which he regards to be the greatest human tragedy. According to him, the atomic bomb is the most dreadful and disregarded monster: “while the truths of the holocaust carried out by the Nazis in Auschwitz against the Jews is very well-known worldwide, the Hiroshima experiences are not so well and deeply known, despite of having had caused so much suffering that exceeds the deeds done at the concentration camps.” [2]

Kenzaburo Oé was not only a renowned fiction writer, but he was also a chronicler, and as such, he visited Hiroshima every year on the anniversary of the atomic bomb explosion, which he regards to be the greatest human tragedy. According to him, the atomic bomb is the most dreadful and disregarded monster: “while the truths of the holocaust carried out by the Nazis in Auschwitz against the Jews is very well-known worldwide, the Hiroshima experiences are not so well and deeply known, despite of having had caused so much suffering that exceeds the deeds done at the concentration camps.” [2]

The chronicle, by definition, is ground level literature, a true story, a detailed portrait and a loudspeaker for the victims. In the Hiroshima Notebooks (1965), Oé presents us the hibakusha testimonies, the atom bomb survivors. These are stories from common people, average Japanese people, mainly patients from the Atomic Bomb Hospital, dedicated doctors, or just young people growing in the shadow of leukemia.

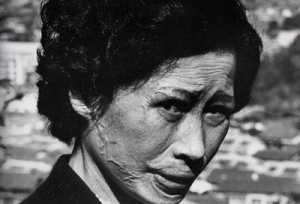

In addition, Oé’s goal was to show the moral character of the Hiroshima inhabitants. He was impressed by their way of living, so humanitarian, and their humanist way of thinking. Oé sees the hibakusha as authentic human beings, and also notes that all the testimonies have a common subject: human dignity. The people included in the Hiroshima Notebooks, “and all the victims that have shared their bitter experiences, even though they did it with modesty and quietly, they have an unmistakable dignity.” [3]

The chronicles reflect the silence and courage before “a desperate worry,” the enormous patience and humility of the survivors, the elegance of their sacrifice without gestures. From the Hiroshima suffering, Oé rescues honorable human beings, generous, authentic, that “despite the difficulties and distrust”, had to work hard and fight tirelessly, even while maintaining their faith in humanity. Within the dignity contained in these stories and within the repetition of stoical behaviors, there is self-restraint, a type constraint, that has been pointed out as one esthetical and ethical trait of the Japanese civil society. [4]

“When I talk to the victims of the atomic bombs in the varied hospitals where they are being admitted, in their homes, or in the streets of Hiroshima, when I listen to what they have undergone and how they feel, I realize that each one of them has unique qualities to observe and express what the human being symbolizes and represents. I am aware that they understand very well the meaning of words such as courage, hope, sincerity and even tragic death, all words with a deep moral content. In other words, they are moralists. Moralists in the former Japanese sense of the word, that could be translated nowadays as commentator of human way of life.” [5]

The atomic explosion

After the detonation, followed a great brightness, which blinded many people, a blazing shockwave, and then, a huge mushroom cloud was formed. [6] In the valley of Hiroshima, half an hour after the bomb was dropped, the great amount of concentrated hot gas produced a fire storm. Between 11 in the morning and 3 in the afternoon, right during the critical point of the fires, a tornado formed in the north part of the city. The survivors, hurt, blinded, or mutilated, were desperate to drink water and many jumped into the Seven Rivers. Many people drowned. The smoke and the condensed clouds finally dropped the radioactive black rain, this precipitated the radioactivity. It was a black rain, literally, black, thick and full of radiation. The fish died in the rivers, the animals that ate the grass filled with radiation died poisoned and had severe diarrhea problems, all living beings were affected by one way or another by the explosion of the radioactivity.

In the pond (…) carps swam among the dead bodies.

There was a swallow with its wings burnt and could not fly anymore, it only could hop from one place to another.

When I came back to my senses, I saw my partners still greeting standing to attention. I called them, «Hey!,» and I padded one of them on the shoulder. He vanished and became ashes. [7]

The first sicknesses derived from the radiation, which used to end in deadly internal bleedings, increased greatly during the first six months after the bomb exploded. “Right after the bleeding started, the atomic bomb victims were in the verge of death. In the winter that came after the atomic bombarding, the majority of the patients with acute radiation symptoms had died and, apparently, the critical level of radiation sicknesses had being overcome.” [8]

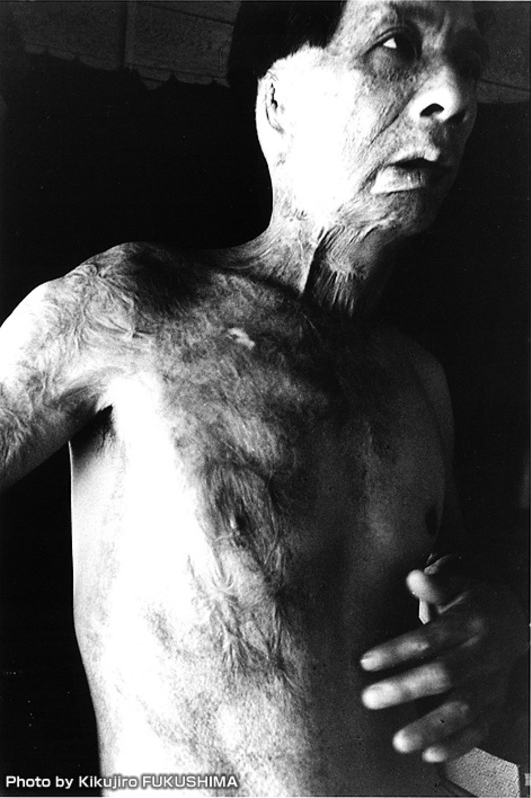

This brief break suggested that the radiation effects had dropped, but afterwards, in 1946, the symptoms increased significantly: hair loss, fever, subcutaneous bleedings, etc. The keloid scars were the first thing that proved that the sicknesses had not disappeared. These scars are the result of an overgrowth of granulation tissue produced during the healing process of a burn. They appeared at the end of 1945 and caused a lot of serious troubles to the hibakusha.

In 1963, almost 20 years later, Mr. Miyamoto, patient at the Atomic Bomb Hospital, declared: “still today many people suffer due to leukemia, anemia, gastric disorders, and they fight while they walk the road to a terrible a death,” [9] meaning: they must fight during all the time they have left until a they suffer a terrible death. “If leukemia strikes, a patient can live between six months and one year. The medical therapies can offer a temporal solution, but not for too long. When the leukocytes increase it is fatal.” [10]

Besides “consumed bone marrows, cancers everywhere in the body, an astonishing number of leukocytes in the blood,” [11] in general, the radiation effects turned a healthy population into dejected human beings, weaken, exhausted. “Frequently, the victims have explained confidentially that before the bombarding they did not suffer any sickness, and afterwards, they did not suffer those symptoms specified by the Ministry, nonetheless, they were not healthy.” [12] The secondary effects of the bomb seem to erode the human body resistance to sicknesses in general. In many cases the patient’s health suddenly deteriorated, provoking a fatal end almost imminent. Any symptom could be considered as an effect of the atomic bomb because the hibakusha’s health was damaged in a very substantial and complex way.

It would not be reasonable to do not consider the mental diseases produced by the atomic bomb another fallout. A man commits suicide jumping into the Seto Island Sea from a ferry’s gunwale. He did not leave a note, only a medical card, the medical record that identifies him as a victim from the atomic bomb. “The man did not show any evident symptom of having suffered a sickness derived from the bomb, but he was distressed permanently for a long of time, that is called atomic bomb neurosis.” [13]

Silenced, forgotten survivors

In November, 1945, at the break of the day, the occupation, the United States Army’s surgical team issued a categorical declaration: “All the people that could die due to the radioactive effects produced by the atomic bomb had died already. Therefore, there will not be no further physiological outcomes attributable to the residual radiation.” The North American announcement was false: for many hibakusha a true torment was about to begin, the slowly poisoning of the radioactive explosion.

The Allies forced the atomic bomb victims to remain silent. When the occupation concluded (1952), and the censorship ended, the victims were already forgotten. Although some research projects were carried out by the Japanese national authorities in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there was not enough public discussion about it, unless not until the United States carried out the Bikini Day (1954).[14] That is when the Japanese population started to worry about the radioactivity effects on the living beings, so the first, basic, official policies were issued in order to help the atomic bomb victims. That “nuclear essay” [The Bikini day] renewed the interest in the subject and lead to the first World Peace Council to be held the following year.” [15] It is 1955, and the hibakusha can offer, for the first time, a story. They have lived through ten years of censorship and oblivion and during this time “…[p]eople that were under the occupation restrictions (…) had to remain silent, and after some years they died quietly.” [16]

Thanks to the enacted Medical Attention Law for the atomic bomb victims, between 1954 and 1964, 367,413 medical check-ups were carried from which 70,309 were thorough exams, and the victims treated as beneficiaries. After these check-ups they received a certification that stated that they suffered medical issues derived from the atomic bombs, and a book which contained treatments related to these issues was handed to the victims. There was no financial support, or any other kind of compensation or consideration.

Offering only medical treatment to a sick person, who is generally alone, could mean very little. For example, from a column in a Hiroshima newspaper called Yomiuri Shinbun, the noon edition on January 19, 1965, Oé rescued the following story:

A 19-year-old girl committed suicide and left a note: “I have been a bother, so I will die as I had planned.” She was exposed to the bomb when she still was inside her mother womb, who died years later after the bombarding.

The girl suffered many sicknesses caused by the radiation; her liver and eyes were affected since her tender childhood. To crown it all, her father left home after her mother died. She lived with her 75-year-old grandmother, with a 22-year-old sister and anther one 16-year-old. The four women managed to live by their own means. The three sisters had to find a job in order to finish high school. The girl who committed suicide did not have enough time to get the appropriate medical treatment, although she had one of those books with treatments that were handed to the atomic bomb victims.

As a certified victim, she had the right to some medical complements, but the medical attention system for the victims does not offer support for daily expenses, therefore, the girl could not focus on receiving the treatment that she needed because she could not stop worrying about struggling to making the ends meet. That lack of support was a failure in the actual policies created to help the atomic bomb victims. Overwhelmed by the burden of the suffering and the poverty, her young life was too exhausted and could not continue forward.” [17]

At the end of the 70’s, it was estimated that in Tokyo there were 10 thousand atomic bomb victims. Since 1962, Tokyo Metropolitan Government offered support to some atomic bomb victims associations, and later it launched varied programs such as, health examinations (1970), infirmary expenses (1973) and medical check-ups for the children of the victims (1974.) That local support was exceptional, and it was the only one offered outside the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, since it is very probable that the exodus from the bombarded and devastated cities with no infrastructure had gone to other places and zones besides the Capital City. There are thousands of not registered cases, victims that never received support or help, deaths so silently as forgotten.

Nowadays no one knows the exact total number of deaths that were caused by the radiation of the atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and there is even less information about the Okinawa victims, who died without medical attention.

The wish to remain silent

Besides those who were silenced and forgotten, there are people who rather die quietly. The victims, of a nuclear bomb or of any other tragedy, can wish to remain silent.

Among the letters that were received at the Sekai magazine editorial department, the first ones to publish these chronicles, there was one particular letter that Oé himself pointed out to be a representation of those people who like to remain silent. Its author, Yoshikata Matsusaka, dermatologist and son of Yoshimasa Matsusaka, also a doctor and mentioned further, wrote in this letter:

“People from Hiroshima rather remain silent until the time to face death comes. They want to be in control of their way of living and dying. They want to avoid their personal tragedy to become one more statistic or another excuse for political fights, like the ones happening in regard with the movement for banning atomic and hydrogen bombs. They do not want to give the impression of being begging just because they are victims. It obvious that reporting their tragedy in order to obtain financial support it’s a more urgent need and matter than just doing it to fight against atomic and hydrogen bombs. (…)”

“The majority of the intellectuals and writers disagreed on us victims remaining silent, and they insisted on reporting our tragedy. I hate those who do not understand our wish to remain silent. We cannot commemorate August 6. The only thing we can do is to spend that day quietly with the dead. (…) We, the people who experienced firsthand the horrors of the atomic bomb, rather remain silent. Or at least only mention just a few words for the records and historical documents. It is logical that the intellectuals that have a stand against war and the proliferation of nuclear weapons that come to the city only on August 6 do not comprehend the way the victims feel.

“(…) I have always told myself that, despite being a victim of the bomb, I cannot allow me the tendency of seeing myself as being victimized, self-pity. I have tried to recover, I have tried getting back to normal. Although I experienced the explosion [Yoshikata Matsusaka was 1 mile away from the hypocenter of the explosion that day, and he immediately showed some radiation symptoms,] I want a death that is not a consequence of the radiation, as any other human being that has not experienced it in his or her own flesh. (…)”

“I also want to remind you that there are victims who do not develop symptoms, who optimistically wish to become normal people again before becoming another statistic in the fight against nuclear weapons.” [18]

In many parts of his chronicles, Oé remembers these quiet victims. They are people “who prefer to forget and who do not want to talk anymore about the imposing explosion and brightness. (…) They need to forget in order to continue with their lives. (…) They have the right to remain silent. They have the right to forget, if that is possible, about everything related to Hiroshima. They have had enough. Some victims, even knowing that the best medical treatments for the sicknesses and symptoms where available in this city, they preferred to live in any other place because they wanted to get away from anything that reminded them about the city internally or externally. They have the right to run away from it.” [19]

Having the eyes on the victims

Toshihiro Kanai, owner and lead writer of the Chugoku Shinbun, a regional newspaper that was published in Hiroshima, considers himself as one of the victims who do not prefer to remain silent. When the atomic bomb was dropped, there were no press devices that could write the words “atomic bomb” or “radioactivity”. Almost 20 years later, during the first World Peace Council, Oé tells us his impression about him: “he has that restrained spirit typical among the lower rank samurais from the epoch of the Meiji Restoration.” [20]

The outrage that his face showed grew during 19 years of resistance, he spent ten years living under censorship and nine years arguing publicly about the atomic bomb. To this leader writer we owe nothing else than the effort of having his eyes on the victims: during that conference in 1964, Mr. Kanai started to prepare a “blank document about the victims and the damages caused by the atomic bomb.” There he developed the following main idea: that the understanding of the atomic bomb should be focused on the suffering that the victims underwent and not on the fascination of its warlike effectiveness.

According to Mr. Kanai, the great power of the atomic bomb is more well-known than the human suffering that it caused. Hiroshima and Nagasaki represent a warlike demonstration, they are synonyms of the devastating effect of the most terrifying massive destruction weapons, and this perspective also includes a kind of embellishment done by the high temperature gases concentrated during its explosion:

Every nation in the world has the tendency to ignore or forget the enormous amount of human suffering provoked by those smaller bombs [the atomic bombs are smaller than hydrogen bombs.] The discussions were focused in identifying the enemies of peace, and therefore, in doing an effort to keep the world very well informed about the experience of being bombarded with this type of weapon because this is being disregarded. In this moment, the burning wish of the victims, in name of all the dead and survivors, is to make sure that people around the world fully understand the nature and extent of the human suffering that an atomic bombarding causes, and not only it destructive capacity. [21]

The “blank document about the atomic bomb victims and damages” was conceived as a wake-up call for the people around the world, while mainly the United States, Russia and China were comparing results from their own nuclear essays. For the lead writer Kanai, the document must include “the supervision over those unsolved problems that the atomic bomb victims had, and also the application of health policies for their treatment and support. The word unsolved presents very wide implications.” [22] In addition, the document should be expressive, it should contain the bitter words and complaints, it should include the “secondary victims of the radiation that entered both cities shortly after the explosions”, and it should deal with the pressing needs of the second generation: the descendants, born deformed or dead, of those who were exposed to the radiation.

Final words

In this first issue, the tragedy of the atomic explosion was presented from the survivors point of view. We have shared the first moral testimonies, in other words, extraordinary descriptions of the reality. We also presented information regarding the nuclear war crimes.

In the second and last issue, we would share more stories from the nuclear survivors; concluding, in this way, our presentation of the Hiroshima Chronicles, by Kenzaburo Oé, a book that reflects on human suffering and dignity, and alerts us about the human need of global disarmament in order to achieve long lasting world peace.

[1] Takeo Takahashi (1897-1973), a poet that lost his three daughters on August 6, 1945, the older one was pregnant and her husband also died. This poem was written on the first anniversary of their deaths. (English Trans. by Ma. Teresa Vidaurre, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014.)

[2] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos de Hiroshima. Yoko Ogihara and Fernando Cordobés Trans. Barcelona: Anagrama, 2011, p. 176. (English Trans. by Ma. Teresa Vidaurre, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014.)

[3] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 122.

[4] Within the second issue of José Watanabe, Pequeños Universos dedicated a few lines about how he “praised self-restraint.” From the perspective of the Peruvian poet Nikkei, Bushido and its teachings influenced on the behavior of the civil society, establishing characteristics such as self-restraint and self-control before terrible situations. For more information, click here.

[5] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 83.

[6] Robert Lewis, Enola Gay’s copilot, the Boeing B-29 bomber that dropped the atomic bomb Little Boy, wrote in his diary: “a purple light expanded until it became an enormous and blinding fireball. Its core temperature was 50 million degrees. (…) The cockpit was illuminated with an odd light. It was like a peep into hell. Then, the shock wave followed, an air mass so compressed that it seemed solid (…) When the shock wave stroke the plane, Tibbets [the pilot] and I hold tight to the controls. He [the pilot] raised the plane to its maximum height. The mushroom had already risen to a height of 1 mile, and was still boiling upwards like something terribly alive. The city was underneath all that. My God, what have we done?” (English Trans. by Ma. Teresa Vidaurre, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014.

[7] Testimony translated from Cuadernos de la bomba atómica. En Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 189. (English Trans. by Ma. Teresa Vidaurre, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014.)

[8] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 142.

[9] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 71.

[10] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 48.

[11] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 65.

[12] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 83.

[13] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 91.

[14] On March 1, 1954, The United States published a nuclear essay in the Bikini atoll, in the Marshal Islands located in the South Pacific. The radioactivity effects were very sever over the 239 inhabitants from the three atolls from that area. 49 people died in the following 12 years. Moreover, 28 North American meteorological observers died, and 23 crew members from a Japanese fishing boat called Lucky Dragon V also died while fishing around that zone.

[15] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 206.

[16] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 77.

[17] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… pp. 170-171.

[18] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 15.

[19] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… pp. 118-119.

[20] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 69.

[21] Toshihiro Kanai. “Presentación del Documento en blanco sobre las víctimas y daños de la bomba atómica.” En Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 71.

[22] Kenzaburo Oé. Cuadernos… p. 71

Pingback: Hiroshima Notebooks, by Kenzaburo Oé. (First Issue) | altracittà